How to think like a genius mathematician

Too many people don’t understand statistics.

Go to any comment section on the internet and you’ll see some user completely misinterpreting a stat to boost their ridiculous political argument.

You don’t need to be a genius to think like one. You need only learn from a mathematician who saved thousands of lives.

Every week was a recurring disaster

The early years of World War II weren’t going well.

Too many bombers were sent screaming to the ground with soldiers trapped inside. Husbands, brothers, and sons had their futures erased in a terrifying 2-minute dive of death.

Allied forces needed a solution. They hired Abraham Wald, a genius who excelled at an early age.

Wald had a Ph.D. in mathematics and was trained by Karl Menger himself (the man who wrote Menger’s theorem and many other lessons from your geometry class).

Abraham was ousted from Austria for being a Jew. In retaliation, he joined the growing list of Jewish scientists who lent their ability to the Allied army. He was assigned to the “Statistical Research Group”, a special government division at Columbia University. Wald’s job was to solve complex, consequential problems that stumped the military’s brightest members.

Leaders isolated and presented Wald with a very specific challenge, “How can we armor B-17s in order for them to survive more missions?”

Wald found a solution

The central constraint was that weight mattered: you can’t just double the armor on a B-17. You may as well strap wings on a tank at that point.

Planes still needed to carry bombs, have range, and be maneuverable. They couldn’t just opt out of missions that looked more dangerous than others.

Wald asked for the repair data on returning B-17s. The flight crews then documented damage to spreadsheets that were sent in.

The reports piled up on Wald’s desk.

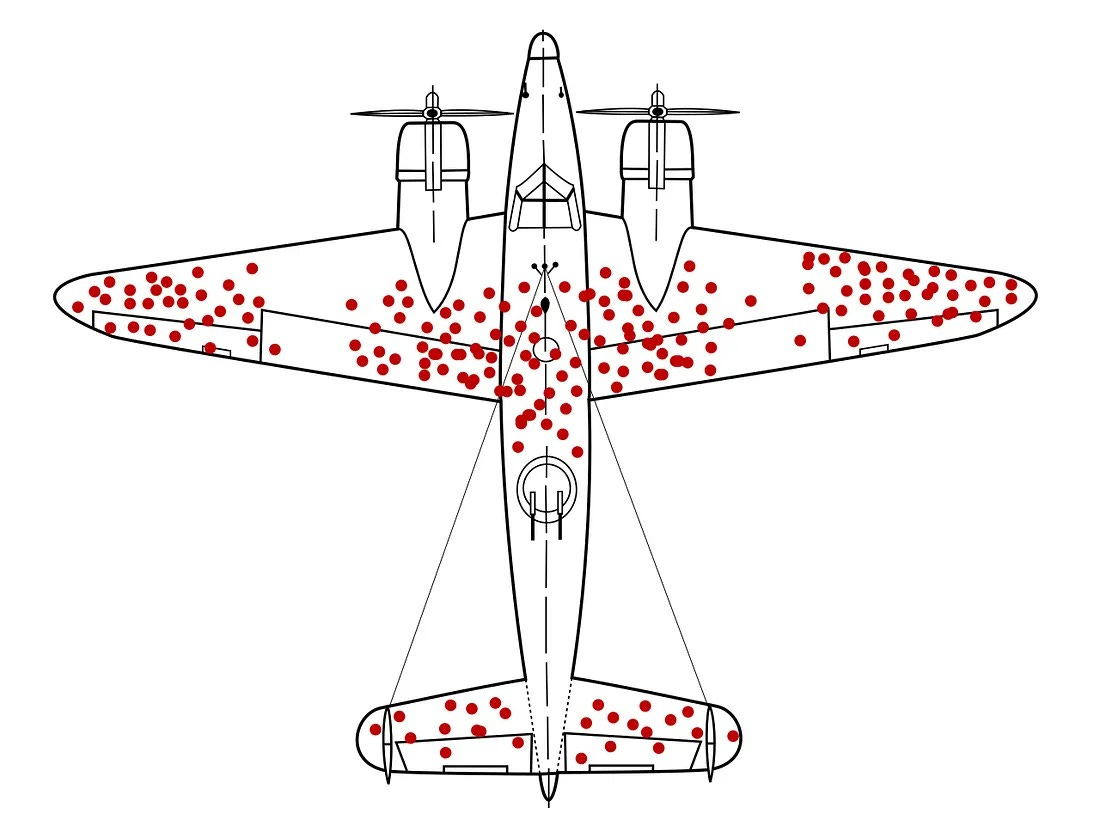

If you look at the grid, the solution might seem obvious: add armor where the plane is taking the most damage. This is what Wald’s advisors suggested.

Wald felt the tingle of doubt as he scanned the data. His intuition sensed a flaw that the other researchers had missed.

He asked a breakthrough question: “Where are the missing holes?”

In theory, every part of the plane should be hit at some point.

The planes had consistent areas that weren’t taking damage. Then he drew a big conclusion: researchers were only getting damage reports on planes that survived.

There were no holes in the other spots because those planes hadn’t made it back. Those were critical areas that should be armored.